18.12.2023

Special Report 96 > First edition

The School of Lausanne : the Heritage of Léon Walras

Léon Walras, a 19th-century economist, is widely recognized as one of the most influential thinkers in the history of economics. A pioneer of modern economic theory, Walras made fundamental contributions that revolutionized the way we understand and analyze economic mechanisms. His innovative ideas laid the foundations for mathematical economics and greatly influenced the subsequent development of this discipline.

Let's dive into the life of Léon Walras and discover his career path: from failed student to recognized economist at the Lausanne Academy, to writer and journalist.

The start of his career: from failure to failure

Léon Walras, born on December 16th 1834 in Évreux, France, was the son of Auguste Walras, a scholar with a passion for economics, who held positions as a philosophy professor and academy inspector. The intellectual environment in which he grew up quickly permeated young Léon, giving him an early insight into economical ideas and philosophical discussions.

Auguste Walras

Walras continued his secondary education at the Collège of Caen, then, as of 1850, at the Lycée of Douai. In 1851, he obtained his Baccalaureat ès Lettres, followed by a Baccalaureat ès Sciences in 1853. Despite his academic success, he twice failed the entrance exam to France's prestigious École Polytechnique in 1853 and 1854. This series of disappointments upset his father and pushes Walras to explore other paths. At his father's request he tried to become an external student at the École des Mines de Paris but failed to gain admission. These repeated failures marked a difficult period for both him and his father. Indeed, Walras' family situation was marked by financial difficulties, including his father's increased responsibility following the death of his other children. The death of his brother Louis in 1858 left Léon as the last surviving child, probably intensifying the expectations now placed on him.

Walras then turned to a literary career, also marked by difficulties and setbacks. In 1856, he wrote a novel entitled "Francis Sauveur", but the manuscript was rejected by the Revue des Deux Mondes, a prestigious literary publication of the time. He nevertheless published it independently, borrowing money from a few admirers and friends. After this setback, he decided (again) to change direction and turned to the in-depth study of economics. His decision was influenced by a conversation with his father, who encouraged him to go into economics.

The turning point: Tax Congress in Lausanne and arrival at the Academy

After a disappointing literary quest in France, Léon decided to earn his living as a publicist, specializing in political economy. He then wrote several articles and a book refuting Proudhon’s thesis. He also managed to get into La Presse, Émile de Girardin's famous newspaper, and the Journal des Économistes. His career seemed to be on the right track.

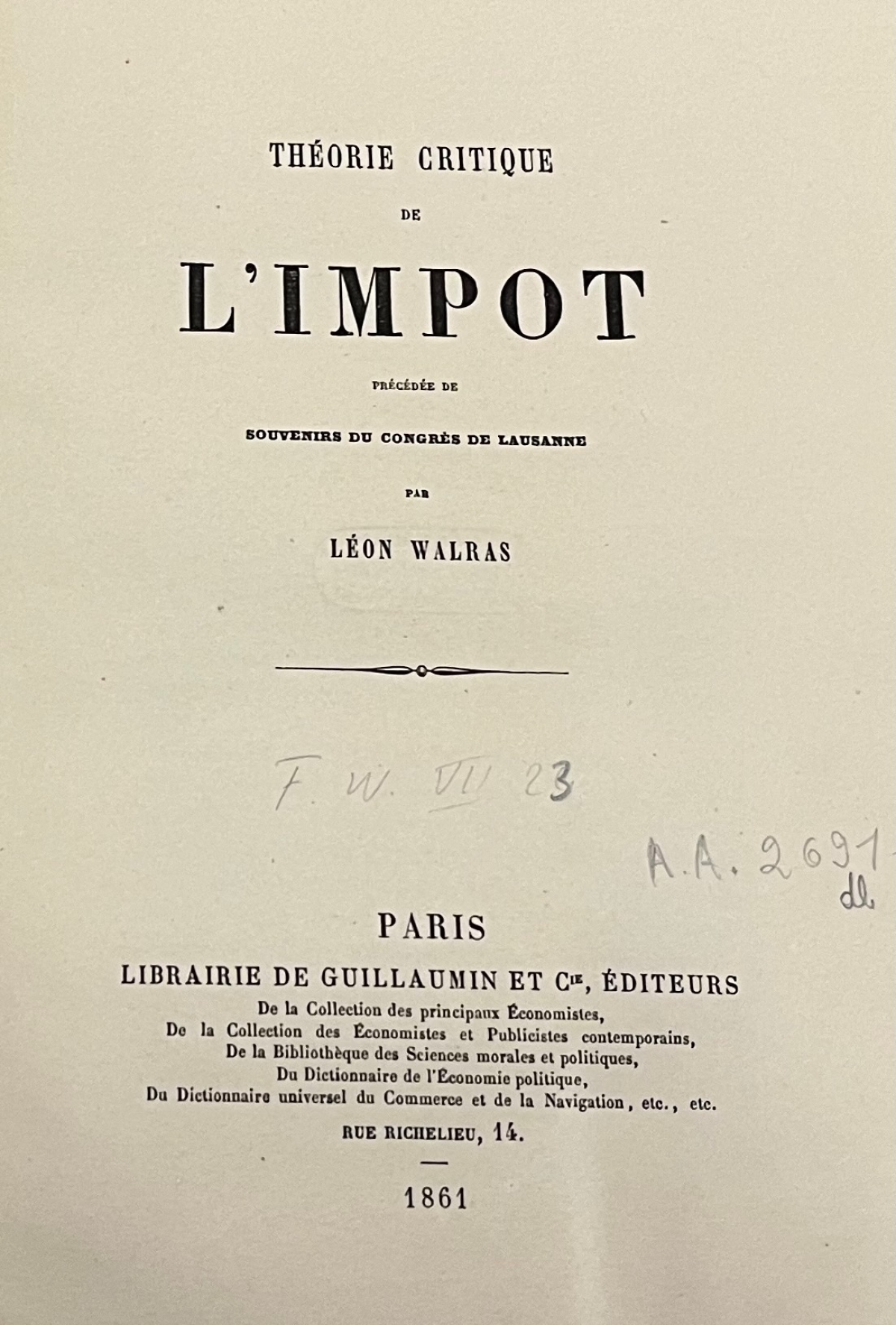

In 1860, Walras' career took a major turn. He decided to take part in the Congress on Taxation in Lausanne, an important event at a time when the Radicals, newly in power, were addressing this crucial issue. The Congress was followed by a competition to find the best tax project for the Canton. Under his father's direction, Léon submitted a dissertation entitled “Théorie critique de l'impôt” (Critical Theory of Taxation). In it, he compared the proposals of Émile de Girardin, director of La Presse, in favor of a capital tax with those of Joseph Garnier, director of the Journal des Économistes, for an income tax. In one session, he alienated his two main employers who accused him of socialism. This put an abrupt end to his brief career as an economics journalist.

Front cover of Théorie critique de l'impôt by Léon Walras

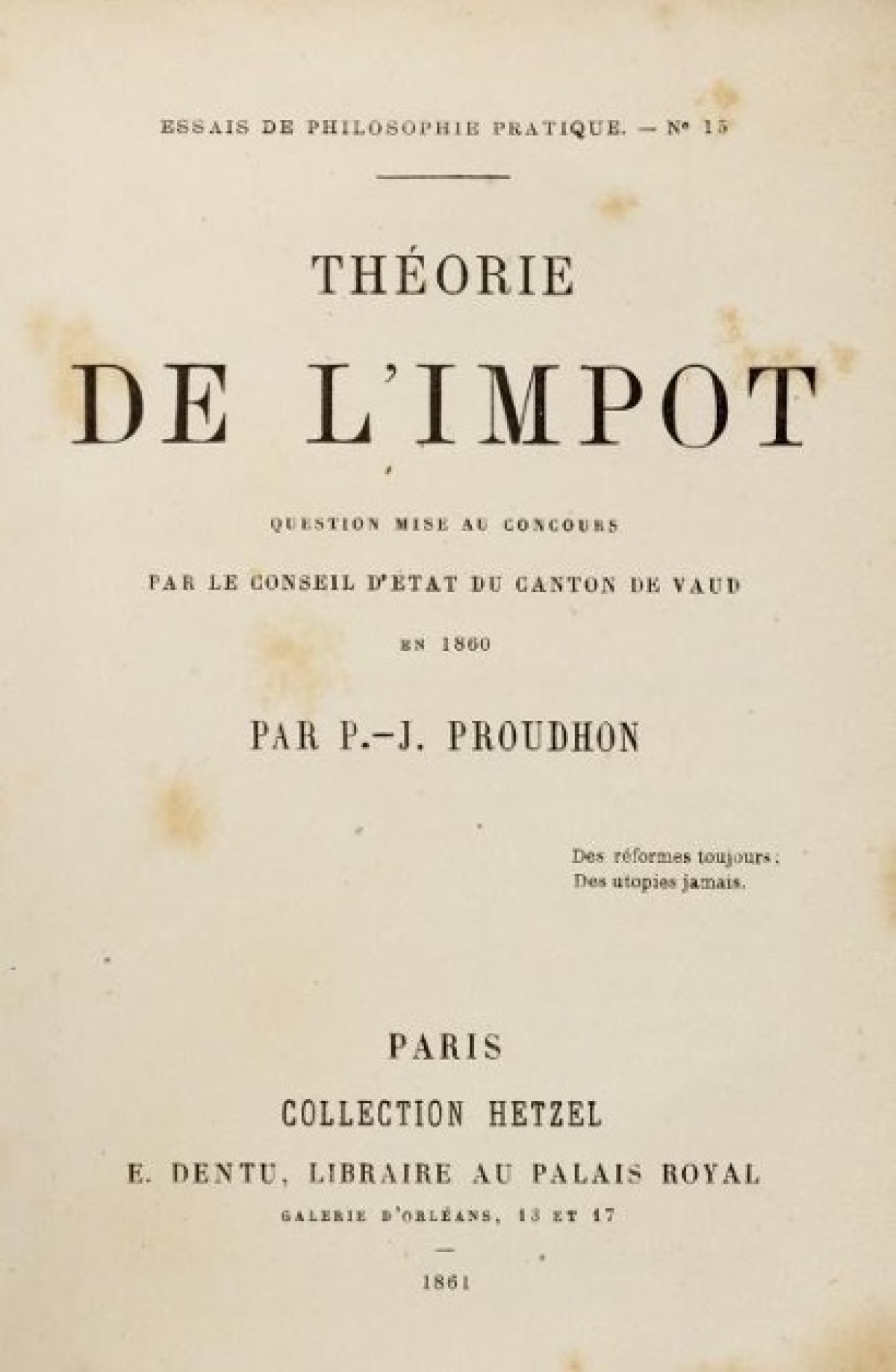

But despite being one of the youngest congressmen his speech was remarkably clear. If his ideas, influenced by those of his father, offend certain sensibilities the way he presents them impresses. His memoir finished fourth (no first place was awarded) behind Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Amédée Lasseau.

Front cover of Théorie de l'impôt by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

At this Congress, he met two people of major importance: Louis Ruchonnet and Jules Ferry who will later become a great friend.

The former is a young lawyer at the start of his career attending the congress sessions in the public gallery (if his name rings a bell, it's because he will become the 26th Federal Councillor). Impressed by Walras' performance - and not having had the opportunity to meet him in Lausanne - Ruchonnet will meet him in Paris to tell him how in awe he had been. Ten years later, in June 1870, having in the meantime become head of the Department of Public Education in the Canton of Vaud and reorganizing the Lausanne Academy, he returned to Paris for another visit and offered Walras a chair in political economy at the Faculty of Law, if he would take part in the competition to obtain it.

In his letter of application, Walras positioned himself more as a researcher than as a professor, believing that economics was still in their infancy. However, because of his socialist convictions, the Council of State refused to appoint him as a full professor, despite the support expressed by Ruchonnet. By a vote of 4 to 3, the decision was taken to appoint Walras as an extraordinary professor. He settled on the shores of Lake Geneva where he taught until 1892.

Development of his theory

Nevertheless, by 1870, it's crucial to remember that Walras was mainly influenced by his father's ideas. At the time, he was essentially the bearer of the concepts of social economics and an ambition to formalize economics mathematically, projects that were the direct legacy of Auguste Walras. In fact, the mere fact of settling in Lausanne represented the fulfillment of a wish rooted in his father's dream.

Let's look back for a moment at the dissertation Walras wrote that enabled him to become an extraordinary professor at the University of Lausanne. The dissertation, entitled "Théorie critique de l'impôt" (Critical Theory of Taxation), was submitted to the Lausanne International Tax Congress, which opened on July 25th 1860. The author's father as well as other thinkers such as Smith and Ricardo are cited at the outset of the work to enhance their contribution to the ideas that Walras later suggested. Right from the introduction to his memoir there are references to his famous "Theory of General Equilibrium" which was to revolutionize economic thought. In it Walras states that "exchange value has its cause not in the fact of labor [...], nor in the fact of utility [...] but in the fact of the limitation in the quantity of useful things. This theory is the true one and the only one from which it can be inferred that exchange value is measured by scarcity or by the ratio of demand to supply". In this extract, we find the important notion of scarcity, one of the pillars of price determination according to Léon Walras.

The main thrust of this work lies in the author's belief in the need to introduce a wealth tax in addition to an income tax so as not to penalize the less well-off social classes by imposing the same level of taxation on them as on wealthy landowners. For example. Walras had already mentioned the advantage of being a landowner in his "Theory of Social Wealth" in the following way: "The conclusion which presents itself is that, in a progressive society, the condition of the landowner becomes more and more convenient [...]. Without taking the least trouble, [...] by the simple fact of the law I have just mentioned, the landowner has the rare advantage of seeing an increase in the exchangeable value of the capital he possesses and in the amount of income this possession assures him".

The quality of this memoir convinced the Vaud State Council to appoint Léon Walras as Extraordinary Professor, as mentioned above.

Influence and posterity

The end of Léon Walras' life was marked by severe financial difficulties. His dedication to spreading his innovative economic ideas led to considerable expenses leaving him almost bankrupt by the end of his life.

To support his family and secure a financial future for his daughter, Aline Walras, he took unusual action. In 1906, in a desperate attempt to secure his livelihood, Walras applied for the Nobel Peace Prize. It may seem surprising, but he was aware that the French economist Frédéric Passy had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901. This was probably motivated by the need to receive the monetary award that accompanied the prize, in the hope of solving his financial problems. Unfortunately for Walras, despite his attempt, the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States at the time, for his diplomatic efforts in ending the Russo-Japanese War. Walras' attempt to win the Nobel Peace Prize was unsuccessful, failing to produce the hoped-for financial solution.

However, his candidacy did result in a book, "Peace through Social Justice and Exchange", published in 1907. Although this attempt failed to resolve his financial problems, it marked the tragic ending of a man whose contributions to economics were essential but who unfortunately ran into financial difficulties at the end of his life.

So why wasn't he widely recognized during his lifetime? For several reasons.

Firstly, his revolutionary approach to economics, based on the use of mathematics to model economic interactions, was ahead of its time. At a time when economics was mainly studied qualitatively, the introduction of mathematical concepts and the rigorous formalization of economic ideas were quite uncommon, if not misunderstood by many. Secondly, his ideas diverged from the mainstream of classical economics at the time. His approach to general equilibrium and his insistence on mathematical modeling were out of step with the prevailing methods and ideas of the time, which often led to the relevance and value of his work being underestimated by his peers. Thirdly, his socialist convictions may have limited his recognition in a political and academic context where such positions were often viewed critically or even hostilely.

However, after his active period in the early 20th century, economists such as Vilfredo Pareto, who succeeded Walras at the University of Lausanne, and others recognized the importance of his contributions. The change in the intellectual and academic landscape, with increasing openness to new approaches and methods in economics, has led to a reassessment of his work. The revival of interest in his ideas eventually led to posthumous recognition of his major influence on the development of modern economic theory.

And where does the University of Lausanne fit in?

Walras' intellectual commitment and groundbreaking work helped shape the academic identity of the University of Lausanne. The academic freedom he enjoyed and the recognition of his expertise have also left their mark on the institution, offering a model of scientific rigor and intellectual innovation. Beyond economics, Walras' legacy has had a wider impact on UNIL, stimulating an academic environment suitable for the exploration of new ideas, encouraging intellectual daring and innovation in diverse fields of study.

Léon Walras remains a founding figure, whose influence continues to be felt at the University of Lausanne, both through his major intellectual contributions and through the inspiration he provides for research, reflection, and the advancement of knowledge in academia.

Gwendoline Munsch, Elias Kerbage, Samantha Cotter, Valentin Mermoud

Bibliography

Bridel, Pascal. Essais sur l’histoire de la pensée économique : un nain sur les épaules de géants. Classiques Garnier, 2022.

Busino, Giovanni, and Pascal Bridel. L’Ecole de Lausanne de Léon Walras à Pasquale Boninsegni. Université de Lausanne, 1987.

Dumez, Hervé. L’économiste, la science et le pouvoir : le cas Walras. Presse univ. de France, 1985.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. Théorie de l’impôt : question mise au concours par le Conseil d’Etat du Canton de Vaud en 1860. Office de publicité, 1861.

De l’Académie à l’Université de Lausanne, 1537-1987 : 450 ans d’histoire : [exposition], Musée historique de l’Ancien-Evêché, Lausanne, 1987. Éditions du Verseau, 1987.

Histoire des pensées économiques / Les fondateurs. Sirey, 1988.